There has been plenty of discussion about the apartment buildings popping up around James Garner and Boyd Street. Some say they are bad for the environment. Others say they are ugly and do not fit the character of the neighborhood, or that they are crimes against historical preservation. Or - ironically - that higher density is bad for traffic.

What many people seem to overlook is just how valuable it is to introduce incremental growth to a neighborhood. As I was “doom-scrolling” Zillow one random day, I saw a house on Jenkins (off market), which had 10 bedrooms and 5 bathrooms. Upon closer inspection, you can tell there have been a couple of add-ons, and even what appears to be *gasp* an Accessory Dwelling Unit, or “ADU,” in the back. This property sacrifices its backyard to house more people. This allows the property owner to house 10 people on less than 1/6 of an acre. What is surprising about this is, if you were walking in front of this house, you would never guess 10 people were living there. It looks just like any other house in the area:

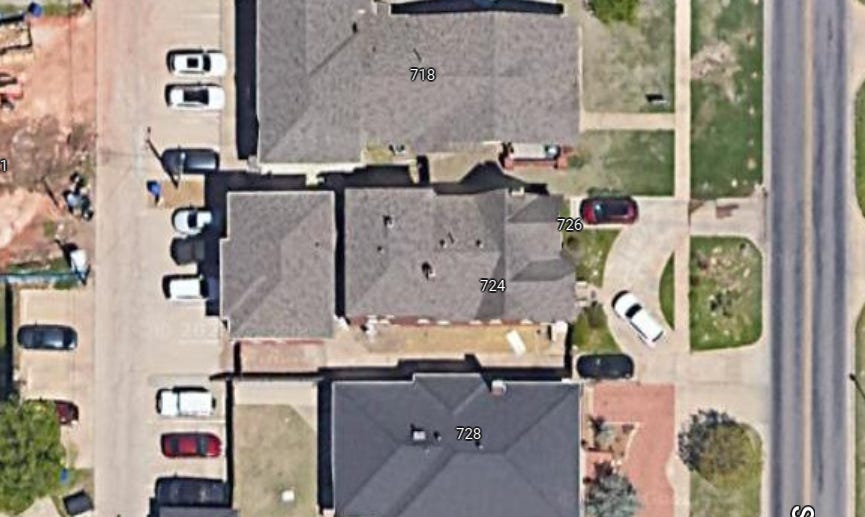

Looking at the aerial view, you can see how this property makes efficient use of the site to house 10 people:

Now, let’s compare 724 Jenkins Avenue to a newer home in Norman of a similar lot size:

With a gentle amount of density, the Jenkins house is three times as productive to Norman than the typical suburban home. That goes for its financial value, and its efficiency at housing people. In the midst of a housing affordability crisis, which type of housing do you think we should we be giving more attention to? This doesn’t even account for the amount of infrastructure required by each home type. Consider that the home on the right is in a neighborhood full of cul-de-sacs and wider streets. Its lower density means more miles of pipeline to provide water, sewer, and storm drainage to each person. It is also farther away from essential services, which forces everyone to get around by car, (commonly known as “car-dependency”), which means more driving trips, which means more road construction, widenings, and highway expansions. It drains the city budget by asking for the same amount of infrastructure and city services for relatively few people. Three times fewer people, to be exact. Which of these properties do you think subsidizes the other?

Developments that force everyone into a car also means ample amounts of parking both on site, and at every destination. Parking lots do nothing to house people, generate wealth, enhance the beauty of our town or the general happiness of our residents. You might consider the environmental impacts of this too: While many people assume higher density is bad for the environment, it is actually low density sprawl that paves the most land, puts the most gas-guzzlers on the road, puts out the most emissions, causes more flooding issues, and also harms water sources due to inefficient land use taking up more of our land overall. That is according to the EPA.

With a gentle amount of density, 724 Jenkins Avenue is three times as productive to Norman than the typical suburban home.

The home on 724 Jenkins is built on gridded streets, and puts more people in proximity to essential services, thereby reducing car trips and giving people the freedom to choose how they want to get around. Since car ownership is optional, those who cannot afford to - or do not want to - own a car are not forced to. In core Norman, walking, biking or taking the bus is much more realistic than on the car-dependent, suburban outskirts. When it comes to housing affordability, transportation costs should always be taken into consideration. While homes in car-dependent suburbia might look cheaper, most people there are now annually spending more than $10,000 for each car they own. Whereas in core Norman, it would be easier for a household to be a one-car family, or even car-free if they wanted to.

Instead of scraping the site as a whole, the developer chose to keep the older part of the house in front, and simply add on to it. If you’re walking in front of this house, it is nearly impossible to tell there are 10 people living there. It just doesn’t look busy, and it isn’t what people typically think of when they think of density. Now, one might say both properties fulfill a need in terms of housing types. One is more oriented toward family housing, while the other might be better suited for student housing. Well, that doesn’t exactly close the gap here, either. 724 Jenkins still has at least two separate units on site with the Accessory Dwelling Unit, thus, if used for multi-family housing, can house two families there. The point of this is to show that “denser” housing doesn’t have to look busy, and this property at 724 Jenkins does a great job of utilizing space discretely.

Why Does This Matter?

724 Jenkins shows us the value of legalizing Accessory Dwelling Units, and other ways to create gentle, incremental density. The type of density that doesn’t radically change the character of a historic and charming neighborhood in core Norman. It really doesn’t take much to create more productive places. That is, places that contribute more to Norman’s long-term fiscal sustainability. This property is doing more to help with our housing affordability problem than any other new suburban home on the fringes of Norman, and this 0.16 acre lot produces three times the revenue for the city than the more suburban 0.16 acre lot. With a limited city budget, complaints about the lack of sidewalks, crumbling streets and bursting waterlines, this is something small we can do to help with those problems. Increasing density is good for our economy.

Often times you might hear developers reference the housing affordability crisis as a reason to approve new suburban housing on the fringes. Well, Norman could theoretically double its housing supply just by legalizing Accessory Dwelling Units city-wide. Instead of taking up what little remaining land Norman has with the most inefficient housing type, we could build developments that house three times the number of people, use less land, and create fewer infrastructure liabilities.

We can continue to build low-density housing and raise our taxes to pay for more bonds to rehabilitate our crumbling streets, bridges, and waterlines. Or, we can start building places that pay for themselves, so that we are not burdening everyone with higher taxes in the future.

*The math:

Property taxes were sourced from Cleveland County Assessor

Approximate “sales tax revenue per acre”:

Although houses by themselves do not exactly bring in sales tax for Norman, you can estimate the amount of money one person in each household spends based on Norman’s annual budget to get an average:

($95 million in sales tax revenue) / (131,449 people) = $722.70 sales tax revenue per person. For 10 people on 0.16 acres, ($722.70 per person) x (10 people) / (0.16 acres) = $45,168 sales tax revenue per acre.

Thank you so much for listing the way you got your math, and what assumptions you used. This makes it so much easier to "do the math" on our own local situations.

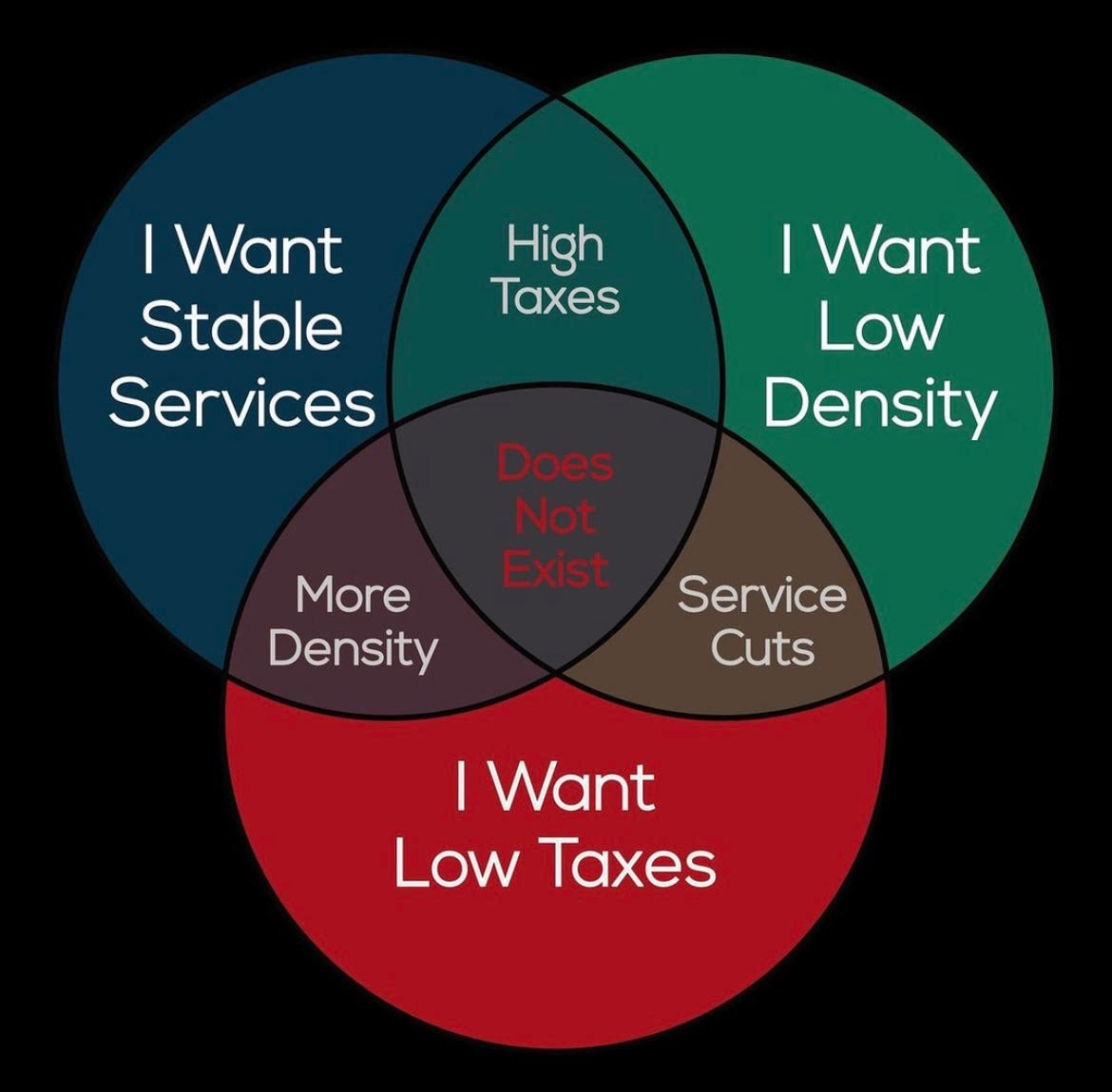

I was also really impressed by the elegance of your Venn diagram. I've been trying to explain this concept in our local debates, and this is the most elegant depiction I've ever seen of the true tradeoffs involved. Thank you!